There’s no denying this: Margaret Atwood is She Who Can Do No Wrong. At least, as far as her fans are concerned. Everyone who isn’t her fan is probably someone who hasn’t read her work. Or so feel her fans.

(See where this is going?)

Atwood has been steadily producing work of incredible literary quality and imagination since her first novel in 1969, Edible Woman. Ten years later, her fourth novel Life Before Man was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award in her native Canada but it was 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale which won not just the Governor General’s Award but also the Arthur C. Clarke Award and was shortlisted for the Booker. That Atwood was a force to reckon with couldn’t have been any clearer. Incredible vision, serious writing chops and the ability to be startlingly prescient is something she’s now known for in every sort of fandom, but there are still people who haven’t yet read her work—shocking, I know! Her latest novel is the hilarious, disturbing The Heart Goes Last, which began life as a serialised story for Byliner—Atwood isn’t one to be left behind by technology either.

So where do you start if you are new to a writer with such a large canon of work? Do you even attempt them all? The thing is, you’ll know in a novel or two whether Atwood’s blend of deadpan humour, searing sharp socio-political commentary and introspective depth is for you or not, but you’ve got to find out for yourself, right? Let me give you a head’s up though. It’s hard to like her work if you’re not a feminist. It’s hard to like her work if you think there is only reliable story, only one reliable perspective and that the narrator is immediately trustworthy. It’s impossible to like her work if you genuinely believe that everyone is ultimately good—or that everyone is ultimately evil.

Here are some suggestions where to start.

The Handmaid’s Tale (1985)

More relevant now than it was when it was first published, this remains Atwood’s pièce de résistance for me, possibly because it was the first Atwood novel I read and the one that made me go begging aunties travelling abroad to bring me back her other books. By the end of this book I was half in love with the writer, whose author photo on my raggedy paperback was of a woman whose eyes were shadowed under a hat, as if hiding something I desperately needed to know. What was this incredible story, where did it fit into what I knew of literature? It was everything I didn’t get from the beloved speculative dystopias I had read and reread until then—Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World. The Handmaid’s Tale was written by a woman, narrated by a woman, about the power balances between genders, about the politics of fertility and the subjugation of women by men in power. It was about a woman trying to gain back her agency, her independence and control of her womb. The worldbuilding was solid, the narrative voice was so very believable and living in Pakistan as a 17 year old who was realising more and more that she couldn’t be out alone, she couldn’t do just what she wanted, that being a girl was pretty damn limiting here, I was obsessed with Offred and her particular, peculiar set of limitations in a country that was once considered one of the most liberal of all.

More relevant now than it was when it was first published, this remains Atwood’s pièce de résistance for me, possibly because it was the first Atwood novel I read and the one that made me go begging aunties travelling abroad to bring me back her other books. By the end of this book I was half in love with the writer, whose author photo on my raggedy paperback was of a woman whose eyes were shadowed under a hat, as if hiding something I desperately needed to know. What was this incredible story, where did it fit into what I knew of literature? It was everything I didn’t get from the beloved speculative dystopias I had read and reread until then—Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World. The Handmaid’s Tale was written by a woman, narrated by a woman, about the power balances between genders, about the politics of fertility and the subjugation of women by men in power. It was about a woman trying to gain back her agency, her independence and control of her womb. The worldbuilding was solid, the narrative voice was so very believable and living in Pakistan as a 17 year old who was realising more and more that she couldn’t be out alone, she couldn’t do just what she wanted, that being a girl was pretty damn limiting here, I was obsessed with Offred and her particular, peculiar set of limitations in a country that was once considered one of the most liberal of all.

The Handmaid’s Tale is set in the Republic of Gilead, once the USA but now a theocracy founded on conservative religious extremism. With fertility on the decrease, young women who may still be able to bear children are recruited as ‘handmaids’, a role that lies somewhere between concubine and surrogate mother. Offred, the handmaid whose tale we are reading, is enlisted to bear children for the Commander, one of the men leading the military dictatorship. Her own child has been taken away from her, she isn’t allowed to read or write or attempt any meaningful connections with anyone at all—no friends, no family, no lovers. All she is to the state, to those around her is a uterus that has previously proved it can bear a healthy child. Atwood explores not just the politics of this situation but also the desperate methods with which Offred (we never know her real name) attempts to gain back her sense of self.

“Now we walk along the same street, in red paid, and no man shouts obscenities at us, speaks to us, touches us. No one whistles.

There is more than one kind of freedom, said Aunt Lydia. Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it.”

The Heart Goes Last (2015)

This idea of freedom to versus freedom from is further examined in Atwood’s latest novel The Heart Goes Last, a madcap dark comedy set in the near future where American civilisation has fallen apart and a young couple are forced to move into a strange artificial gated society to escape the dangers of the ordinary world. They don’t really have freedom to do much more than what is ordained to them once they are inside the town of Consilience, where they spend a month as ordinary citizens and a month as inmates of the Positron prison, though they are free from the gangs that roam the outside streets, free from living in perpetual fear and sudden poverty in their car. But Charmaine begins an affair with the man who lives in their home while she and Stan are in Positron, and Stan begins to fantasise about who he imagines the female alternate resident of their house to be. Throw in a gang of Elvis impersonators, sexist ‘prostibots’, brainwashing techniques to make a woman love you and you’ve got a hilarious, frightening merciless look at modern society.

This idea of freedom to versus freedom from is further examined in Atwood’s latest novel The Heart Goes Last, a madcap dark comedy set in the near future where American civilisation has fallen apart and a young couple are forced to move into a strange artificial gated society to escape the dangers of the ordinary world. They don’t really have freedom to do much more than what is ordained to them once they are inside the town of Consilience, where they spend a month as ordinary citizens and a month as inmates of the Positron prison, though they are free from the gangs that roam the outside streets, free from living in perpetual fear and sudden poverty in their car. But Charmaine begins an affair with the man who lives in their home while she and Stan are in Positron, and Stan begins to fantasise about who he imagines the female alternate resident of their house to be. Throw in a gang of Elvis impersonators, sexist ‘prostibots’, brainwashing techniques to make a woman love you and you’ve got a hilarious, frightening merciless look at modern society.

The Robber Bride (1993)

Three women who couldn’t be more different are united by a fourth—Zenia, the robber bride who at some point in time has stolen each of the others’ boyfriends/lovers away from them. But more than that, she’s destroyed their trust, their goodwill and whatever friendship and loyalty they thought they had towards her. Manipulative, fiercely intelligent and a complete liar, Zenia is an incredible, fascinating character—one of Atwood’s best, I maintain. Is she a desperate sociopath? A cruel mercenary who will do anything to survive? Is she the necessary evil that forces each of the other women to become who they need to be? We as readers know no more than the characters in the book do, which makes Zenia all the more intriguing, especially when we realise she’s been duping us all along, too. Atwood deftly examines female friendship, feminism and power plays in The Robber Bride, all the while winding in the fairy tales she so clearly loves.

Three women who couldn’t be more different are united by a fourth—Zenia, the robber bride who at some point in time has stolen each of the others’ boyfriends/lovers away from them. But more than that, she’s destroyed their trust, their goodwill and whatever friendship and loyalty they thought they had towards her. Manipulative, fiercely intelligent and a complete liar, Zenia is an incredible, fascinating character—one of Atwood’s best, I maintain. Is she a desperate sociopath? A cruel mercenary who will do anything to survive? Is she the necessary evil that forces each of the other women to become who they need to be? We as readers know no more than the characters in the book do, which makes Zenia all the more intriguing, especially when we realise she’s been duping us all along, too. Atwood deftly examines female friendship, feminism and power plays in The Robber Bride, all the while winding in the fairy tales she so clearly loves.

Cat’s Eye (1988)

This is the second of Atwood’s two novels that explore the impact of young women’s relationships with each other on their adult lives, but Cat’s Eye came before The Robber Bride, almost as if Atwood was working up to the more grown-up version of the relationships she explores here. Cat’s Eye follows feminist painter Elaine, as she returns to her hometown for a retrospective of her work and recollects her childhood friends, girls who were (to use a term that didn’t exist back then), her frenemies. The novel explores identity, belonging and female friendship in ways only Atwood can—fraught emotion hidden under brutal honest reality. This one is for anyone who has had childhood friends they needed as much as they shouldn’t have. And let’s face it—who hasn’t had frenemies?

This is the second of Atwood’s two novels that explore the impact of young women’s relationships with each other on their adult lives, but Cat’s Eye came before The Robber Bride, almost as if Atwood was working up to the more grown-up version of the relationships she explores here. Cat’s Eye follows feminist painter Elaine, as she returns to her hometown for a retrospective of her work and recollects her childhood friends, girls who were (to use a term that didn’t exist back then), her frenemies. The novel explores identity, belonging and female friendship in ways only Atwood can—fraught emotion hidden under brutal honest reality. This one is for anyone who has had childhood friends they needed as much as they shouldn’t have. And let’s face it—who hasn’t had frenemies?

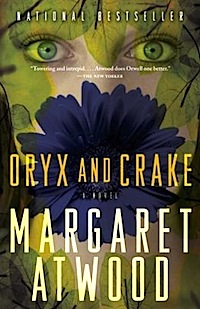

Oryx & Crake (2003)

This was the first in the MaddAddam trilogy and is now being developed for HBO by Darren Aronofsky. Atwood had headed into dystopia before with The Handmaid’s Tale, but with Oryx & Crake she is straight up prophetic. In a world that has been destroyed by a single mad genius, a man known as Snowman appears to be the only survivor, living alongside a tribe of genetically engineered, peaceful almost-human creatures. The novel flashes back to when Snowman was a young boy called Jimmy, playing video games in a corporate compound with his best friend Crake, who grows up to be the mad genius of the story (no spoilers here!). Oryx & Crake features incredible worldbuilding, sharp as tacks humour and some glorious writing—all the things we associate with Atwood at her best. This isn’t just a parable for where our world could go (and is going) wrong—it’s a brilliant speculative and relevant adventure story.

This was the first in the MaddAddam trilogy and is now being developed for HBO by Darren Aronofsky. Atwood had headed into dystopia before with The Handmaid’s Tale, but with Oryx & Crake she is straight up prophetic. In a world that has been destroyed by a single mad genius, a man known as Snowman appears to be the only survivor, living alongside a tribe of genetically engineered, peaceful almost-human creatures. The novel flashes back to when Snowman was a young boy called Jimmy, playing video games in a corporate compound with his best friend Crake, who grows up to be the mad genius of the story (no spoilers here!). Oryx & Crake features incredible worldbuilding, sharp as tacks humour and some glorious writing—all the things we associate with Atwood at her best. This isn’t just a parable for where our world could go (and is going) wrong—it’s a brilliant speculative and relevant adventure story.

And if you prefer short fiction as a taster menu to a writer’s work, check out the astute ‘tales’ of 2014’s Stone Mattress, with stories about ageing, murder, mutation—they’re glinting sharp little stories, polished and smooth. If you prefer poetry, then maybe check out Power Politics from 1971, a collection that contains her most quoted simile:

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

a fish hook

an open eye

Of course, I think you should read all her work right away. But hey, any of these would be a great start. You may never stop, of course, so feel free to blame me for any Atwood addictions you may form.

Mahvesh loves dystopian fiction and appropriately lives in Karachi, Pakistan. She writes about stories and interviews writers the Tor.com podcast Midnight in Karachi when not wasting much too much time on Twitter.